B vitamins are a group of water-soluble micronutrients essential for a healthy metabolism. Among them, vitamin B1, also known as thiamin, plays a key role in energy production and nerve function. (1) Thiamin facilitates the conversion of carbohydrates into glucose, supplying the brain and body with the energy it needs.

Besides fueling your daily activities, adequate levels of vitamin B1 can support heart health, cognitive performance, and psychological well-being. (2, 3)

But what happens when you fall short on thiamin? In this blog post, we'll delve into the symptoms, causes, and remedies for thiamin deficiency.

Symptoms of Thiamin Deficiency

Mild Thiamin Deficiency

In the early stages, a deficiency in vitamin B1 often presents with non-specific symptoms, making it easy to miss. If you're experiencing any of these, it may be a sign that you're running low on vitamin B1:

Fatigue and weakness: thiamin is essential for converting carbohydrates into energy. When thiamin is deficient, this process is impaired, leading to a decrease in the production of energy. As a result, you may experience an overall sense of weakness and fatigue. (4)

Mental confusion: When thiamin levels are low, neurotransmitter production is compromised, leading to an increased risk of cognitive dysfunction. This can manifest as confusion, difficulty concentrating, and memory problems. (5)

Mood changes: The disruption of the balance of neurotransmitters in the brain also impacts mood regulation. These alterations can result in mood swings and hyper-irritability. (6)

Loss of appetite: The digestive tract relies on thiamin for the proper breakdown of food. Lack of thiamin may result in reduced appetite and lead to food intolerances. (7)

Muscle weakness and pain: Thiamin aids in the production of a molecule known as adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which provides energy for muscle contractions. When thiamin is deficient, the muscles may not receive an adequate supply of energy, leaving you with weakness, cramps, and aching. (8)

Severe Thiamin Deficiency

Vitamin B1 deficiency in its severe form can lead to two distinct conditions: Beriberi and Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome. These conditions result from different manifestations and stages of thiamin deficiency.

Beriberi

Beriberi primarily occurs when a person doesn't get enough thiamine over a long period of time. In some cases, it can be passed down genetically. Historically, beriberi used to be more common in places where people ate a lot of white rice. That's because when rice is milled to make it white, it removes most of the thiamin. (9)

There are two types of this condition:

Dry Beriberi primarily targets the nervous system, which can result in muscle weakness, tingling or numbness in the hands and feet, and difficulty walking.

Wet Beriberi primarily affects the cardiovascular system and can lead to symptoms like heart failure, swelling (edema), and difficulty breathing. (10)

Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome

Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome is typically linked to chronic alcoholism. Excessive alcohol consumption can lead to poor nutrition and impaired thiamin absorption, which are contributing factors to this condition. (11)

Part of the syndrome, called Wernicke's Encephalopathy is an acute and potentially life-threatening condition characterized by confusion, ataxia (unsteady gait), and abnormalities in eye movements.

Korsakoff Syndrome, on the other hand, is a chronic and often irreversible condition. It's characterized by severe memory problems, confabulation (creating fabricated stories to fill gaps in memory), and difficulty in learning new things.

Causes of Thiamin Deficiency

Some of the most common risk factors for developing vitamin B1 deficiency include:

Inadequate Dietary Intake

One of the main reasons people might not get enough vitamin B1, or thiamin, is simply not eating enough of the right foods. Foods rich in thiamin include whole grains, legumes, nuts, lean meats, and fortified cereals. However, excessive refinement of cereals can lead to a large loss of B vitamins. Which explains why populations, particularly in specific regions of Asia and Africa, that are heavily reliant on polished rice or cassava, face a bigger risk of thiamin deficiency. (12)

In developed countries, Vitamin B1 deficiency is relatively uncommon among healthy individuals. Most people can easily get foods rich in thiamin, and a lot of the flour used in foods is fortified with extra vitamins, which is the norm in most countries. (13)

Chronic Alcohol Consumption

Excessive and prolonged alcohol consumption can really interfere with how thiamin works in your body. It not only stops thiamin from changing into the form your body can use, but it also causes it to break down faster in your brain. And because of alcohol's detrimental effect on the gut lining, it may make it harder for your body to absorb thiamin in the first place. (14)

Digestive Disorders

Conditions like Crohn's disease, celiac disease, and persistent diarrhea can impair the body's ability to absorb thiamin from the food you eat. (15)

Diabetes

Elevated blood glucose levels in diabetes can cause the body to get rid of more vitamin B1 through urine. Resulting in less overall bioavailability for the body. Some studies show that diabetic individuals may have thiamin plasma levels as much as 75% lower than those in healthy individuals. (16)

Older Age

While the exact reasons remain somewhat uncertain, older individuals seem to be more at risk of thiamin deficiency. (17)

Remedies for Thiamin Deficiency

Dietary Changes

Adding thiamin-rich foods to your diet is a straightforward way to address dietary insufficiencies. Include whole grains like brown rice, whole wheat bread, and oatmeal, as well as legumes like lentils and beans. Lean meats, nuts, and seeds are also considered good sources.

Here are some examples of foods providing a high percentage of the recommended Daily Value (DV) for vitamin B1:

Pine nuts: 52% DV per 100g

Sunflower seeds: 39% DV per 100g

Pecan nuts: 46% DV per 100g

Whole-wheat flour: 42% DV per 100g

Ground flaxseed: 45% DV per 100g

Whole-grain oats: 34% DV per 100g (18)

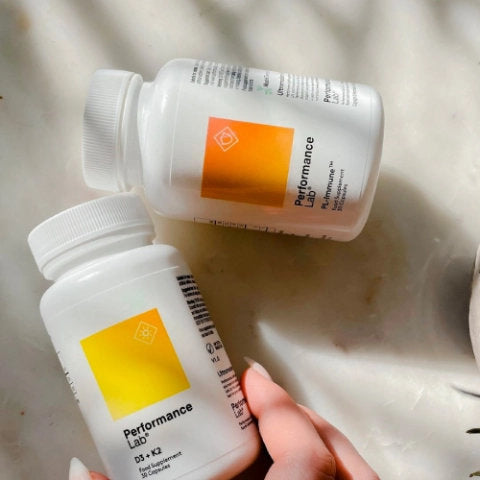

Supplementation

If changing your diet isn't enough or is difficult to manage, thiamin supplements may be recommended. Opting for a B-complex or a quality Multivitamin can provide a practical means to ensure you're getting the right amount of B1.

Limit Alcohol Consumption

If alcoholism is a contributing factor, reducing or eliminating alcohol intake is crucial. This can help improve thiamin absorption and utilization.

Medical Intervention

In cases of severe deficiency or conditions like Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome, immediate medical attention is necessary. Intravenous thiamin may be administered in a clinical setting.

Regular Health Check-ups

For people with conditions that make it hard for their body to absorb thiamin, like a digestive disorder, it's really important to get regular check-ups with a healthcare provider. Monitoring thiamin levels and adjusting treatment plans accordingly can help prevent deficiency.

Final Thoughts

Severe thiamin deficiencies are rare, especially in developed countries, and they typically occur alongside other underlying health issues. Still, it's important to watch out for potential signs that you might be running low on this B vitamin.

The tricky part is that the early-stage symptoms such as fatigue or fluctuating moods can be easily attributed to various factors.

That's why it's so crucial to eat a well-rounded diet abundant in whole foods that that are naturally rich in thiamin. A healthy diet, potentially coupled with a high-quality multivitamin, can be a great way to help prevent any shortages before they start.

Shop Performance Lab NutriGenesis® Multi here

References

- https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/42716/9241546123.pdf?sequence=1

- https://aspenjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0884533608323430

- https://efsa.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.2903/j.efsa.2010.1755l

- https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/full/10.1089/acm.2011.0840\

- https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00207/full?fbclid=IwAR0ljpQNYZ_YsV-WDN_X9TeYmKKdymR6fy75L0VggzqoGgSZ0q8zMtM

- https://biomedgrid.com/fulltext/volume3/thiamin-deficiency-and-benfotiamine-therapy-in-brain-diseases.000621.php

- https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4409/10/10/2595

- https://aspenjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0148607114565245

- https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1525/9780520923645/html

- https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/316/monograph/book/73630

- https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD004033.pub2/ful

- https://nyaspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/nyas.13919

- https://www.nyas.org/media/18948/countries-with-existing-thiamin-fortification-programs.pdf

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6875731/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0899900721000447

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17676306/

- https://europepmc.org/article/med/10791444

- https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/fdc-app.html#/?component=1165